Partyforumseasia: Running a political party is close to impossible without money. Many of the European parties of the 20th century could count on idealism and the support of their members. Reasonable membership fees were being collected by the treasurers of local branches where many members knew many of the co-members and the local leadership. In meetings they could discuss the party goals and develop leadership qualifications themselves and possibly rise in the hierarchy.

Today, that looks nostalgically outdated. Party machineries have grown into sophisticated entities with all the paraphernalia of a real business and turnovers of millions and sometimes billions. Campaigning is a big strategic challenge depending increasingly on state-of-the-art PR and dominance of the media, including the social ones. AI is contributing the icing sugar, and the top candidates develop pop star personas.

Membership fees are not more than a symbolic part of the overall budgets and mobilisation of dedicated members is getting obsolete.

Given these developments, the funding sources for our political parties deserve more attention and scrutiny by the public. Too often, if there are any rules for donations, the parties as well as the donors are not interested in openness and transparency. They prefer to hide the real amount of influence and their vested interests.

Here is an interesting case study from the United States:

Tag Archives: campaign funding

Party Funding in Malaysia and the UK

Irregular practices in the United Kingdom and other countries are no excuse!

Partyforumseasia: The old Romans had a couple of expressions for a basic social strategy which is common until today: “Do ut des” (I give you something so that you give me something back), “quid pro quo” (this for that), or “manus manum lavat” (one hand washes the other). The more popular modern expression in English is “palm greasing” which sounds much nicer than bribery, while the latter is widespread in East and West despite all attempts to fight political corruption.

In the case of party politics in Southeast Asia, the dilemma is that membership and membership fees are not common. Basic funding by members is practically unknown, unlike in Europe, where the traditional parties can still count on contributing members. Meanwhile, election campaigns are getting more expensive year on year, and suitable PR-companies and their helpers have to be paid in cash. Like in the U.S., rich donors help the parties, or more dubious in Southeast Asia, political parties can be bought by rich donors who, of course, expect a return on their investment. “Do ut des…”

These practices are not part of the democratic textbooks but may be stepping stones for a cleaner future with more concern for the voters and the interests of the countries.

Recommended reading, especially for Malaysians:

Party Funding Scandals – UK vs Malaysia (Sarawak Report)

The Conservative party’s biggest donor told colleagues that looking at Diane Abbott makes you “want to hate all black women” and said the MP “should be shot”, the Guardian can reveal.

Frank Hester, who has given £10m to the Tories in the past year, said in the meeting that he did not hate all black women. But he said that seeing Abbott, who is Britain’s longest-serving black MP, on TV meant “you just want to hate all black women because she’s there”….

… Hester, a businessman from West Yorkshire, runs a healthcare technology firm, the Phoenix Partnership (TPP), which has been paid more than £400m by the NHS and other government bodies since 2016, primarily to look after 60m UK medical records. He has profited from £135m of contracts with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in less than four years.

Hester gave £5m to the Conservatives in May 2023 and announced this month a further £5m donation, which had been accepted by the party from his company in November last year. With months to go before the next general election, a party spokesperson confirmed he was now its “biggest ever donor”.

Source: UK Guardian

Our comment

Obnoxious views aside, the emergence of Mr Hester as the largest ever donor to the Conservatives in the UK is reminiscent of much that SR has criticised in Malaysia.

Thankfully for electors in Britain, there are levels of transparency that make matters of such blatant concern more accessible for journalists to draw to public attention.

However, this does not negate the need to confront an apparent perception of over-inflated public contracts being recirculated to the party of government that presided over the issuance of those very contracts. That’s the sort of thing whispered for years in Malaysia.

According to the Guardian, Mr Hester’s wealth has derived from the enormous profits obtained by his company from contracts to supply software services to the publicly funded National Health Service.

Latest recored results show the Phoenix Partnership (Leeds), had a turnover of £75m, with profit before tax of £47m in the year to March 2022.

As the owner, Hester received dividends during the year of £10m on top of a salary of £515,000 which he pays himself as the director.

If Mr Hester is making such enormous margins from these public contracts the immediate concern is that they would appear to be over-inflated. Competitors could surely have been found to perform the same work cheaper.

There is also a potential danger this flamboyant and opinionated businessman may have concluded that generosity towards the ruling party would secure further lucrative work.

Either way, there is a clear reform required to preclude companies in receipt of government contracts, or their owners, from making donations to the party whose ministers signed off on them for at least the duration of that parliament or contract.

If £10 million of public money is to be circled back into party political donations, the money should at least be divided amongst all citizens equally to contribute to the party of their choice: not funnelled through one entity which has just benefitted from an overpriced contract.

After all, this is public money and the public have a right to decide through a majority who gets the most support.

Malaysia is starting its clean up from an even more questionable state of affairs and in order to do so major steps towards transparency, which has regressed in recent years, should be addressed.

The CIDB website, which registers all awards of public contracts and has been made deliberately inaccessible since 2015, ought to be restored to public scrutiny as a first crucial step.

For now, newspapers cannot even report on the sort of matters the Guardian has just shocked its readers within Britain.

11 Mar 2024 Link: Party Funding Scandals – UK vs Malaysia | Sarawak Report

For an overview of party funding practices in Southeast Asia see:

Power Broking in the Shade

Here is a review of the book:

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/732142

- Power Broking in the Shade: Party Finances and Money Politics in Southeast Asia by Wolfgang Sachsenröder (review)

- Risa J. Toha

- Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs

- ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute

- Volume 41, Number 2, August 2019

- pp. 320-322

- Review

Political Funding by Private Donations and Party Preferences

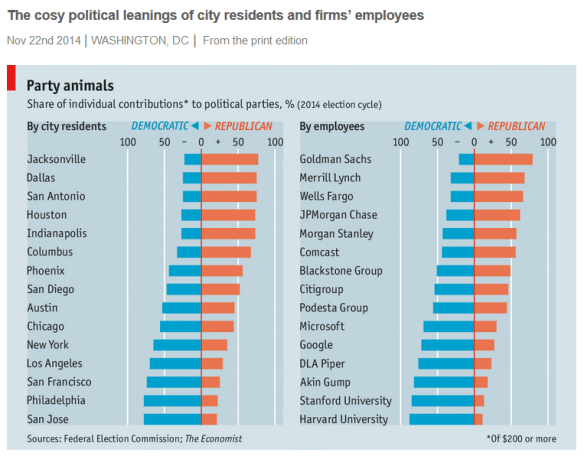

Partyforumseasia strategy-wise: In Southeast Asia private campaign and party donations are certainly not coming in smaller amounts from millions of citizens. The millions here are more investments by cronies and businesses interested in government contacts and contracts. Nevertheless, an article titled “Live together, vote together” in The Economist, November 22d, page 33, is interesting in the way it shows that peer groups can be rather influential on political choices: “Americans who live and work together are often politically like-minded, according to The Economist’s analysis of more than 1.7m individual contributions of $200 or more made during the 2014 election cycle. The analysis also reveals which cities and companies are most politically engaged, financially speaking.” The survey does not correlate its findings with the election results, but at least the more one-sided results are indicators.

In systems with only two parties like the US it is certainly easier to define the areas with better election chances than in splintered multi-party systems. But for political parties in Southeast Asia, apart from the traditional rural – urban divide, it may be useful to study possible partisan clusters in more detail.

One interesting case in point is a pocket of opposition stronghold in the North-East of Singapore, where the Workers’ Party has managed to surf a wave of anti-establishment and anti-PAP feelings and conquer a five seat group representation constituency (GRC) in 2011 plus a single member constituency in a by-election in 2013. The losing PAP normally has a very good grassroots system and its MPs get a feel of the ground in their meet the people sessions every Monday night. Both camps will be trying hard to gauge the voters preferences for the next election which is due by January 2017 latest.

Party and Campaign Funding: Is Malaysia Already a Plutocracy?

Partyforumseasia: International IDEA is very clear about the trend world-wide: Big money is taking over:

“…unequal access to political finance contributes to an unequal political playing field. The rapid growth of campaign expenditure in many countries has exacerbated this problem. The huge amounts of money involved in some election campaigns make it impossible for those without access to large private funds to compete on the same level as those who are well funded.” (See IDEA’s Handbook on Political Finance, freely downloadable from their website. (Link here)

The fact as such is not really new, Julius Caesar used enormous sums for his political maneuvers and was never reluctant to go into debt for their funding. But the proliferation of vested business interests in elections from local to national levels threatens to damage the rationality of policies and a balanced accommodation of the broader interests of a society.

For a case study of Malaysia see the following article in Malaysia Today, 18 September 2014 (Link here): by Rita Jong, The Ant Daily

For a case study of Malaysia see the following article in Malaysia Today, 18 September 2014 (Link here): by Rita Jong, The Ant Daily

In the mid-1990s, a young politician from a Barisan Nasional component party was picked as a candidate for a state assembly seat. Being a newbie, he naively expected that all component parties in the constituency would campaign for him in the spirit of brotherhood. When that didn’t happen, he asked his party elders and found out that he had to first make “contributions” to the branch chairmen of all the parties to help “pay for expenses like petrol and food and beverages”. His rude awakening to the realities of politics came when he found out the going rate then was RM10,000 to RM20,000 per branch, depending on the number of volunteers involved. “I had to dig deep into my own pockets to pay for their help.” The politician learnt fast that there were big companies he could approach for political donations, and he made use of this channel in later campaigns that even involved throwing expensive dinners underwritten by these companies. It seems such a practice is not confined to elected representatives from the ruling coalition, especially after the watershed 2008 general election. A businessman, who declined to be named, told The Heat that in the last general election, he was instrumental in arranging several opposition candidates in Selangor to meet property development companies for donations to fund campaigns. “The sums were not large; between RM10,000 and RM20,000 each. Some donors asked for help to ease approvals for their projects, while others said they didn’t need anything at that time. This meant they would call in a favour if the need arose,” he said, adding that because Selangor is administered by Pakatan Rakyat, it was easier to seek funding. Election candidates do get funds from their parties, but the amount is usually token. Candidates, especially those in “hot” seats and those with a track record to maintain, will go all out for a win, and often have to spend the maximum that is legally allowed, although it is known that many exceed the cap. Just how much is needed? A 2008 court case gives an idea. In that high-profile case, Elegant Advisory Sdn Bhd claimed RM218 million from Umno for the supply of bottled drinking water, mineral water cartons, posters, buntings, and other election paraphernalia for the Barisan Nasional’s 2004 general election campaign. The company lost the suit on the grounds that there was no written agreement. The Election Offences Act (1954) sets the allowed campaign expenses per candidate at RM100,000 for state seats and RM200,000 for federal seats. Going by such figures alone, and the fact there were 505 state seats and 222 parliamentary seats in the 2013 general election, the BN’s maximum allowance expenses would have been about RM95 million. Using the claim by Elegant Advisory as a guide, it is safe to say the BN would have spent much more than RM95 million in GE13. Dr Wolfgang Sachsenroeder, an associate fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore, in a new academic paper published recently, claimed that Umno spent RM1.5 billion in the 2004 election. “Knowing how close the GE13 was expected to be, the estimations of between RM2 billion and RM3 billion don’t seem to be far-fetched,” he wrote. On a request from The Heat, he said the estimations were based on a long list of items like transfers from parties to candidates, transportation, ceramah and concerts, millions of flags and posters, events sponsored by local branches, food and salaries of campaign helpers, cash handouts to the poor, T-shirts and other paraphernalia, and the pay rise for civil servants. He said a big portion of expenses came from state coffers, but there were also a lot of donations from companies. In a paper published in the International Institute’s The Journal in 2003, Linda Lim said political parties in Malaysia “solved this problem by going into business themselves – Umno, MCA and MIC all run some of the biggest business conglomerates in the country, using their political position to earn large profits, part of which are plowed back into electoral campaigns to maintain their political position”. Pakatan Rakyat’s fund-raising is also shrouded in secrecy. Sachsenröder said the component parties of PR had obviously found their own ways to attract funding for their development in the years since 2008 when they managed to challenge the BN dominance for the first time. He said the DAP was probably getting more donations from Chinese businessmen unhappy with the MCA and Umno, while PKR may have received donations from non-Umno-linked businesses and middle-class Malaysians. “PAS has cultivated its image of clean politics for decades and thrifty party management based on volunteer contributions by members.” Despite all this, and considering that all political parties stand to gain from maintaining the status quo, it is unlikely there will be any move to create laws that compel disclosure of campaign funds. It is precisely because of this that the public would not know how such funding affects them later in the form of public policies and enforcement of rules. As American political journalist Theodore H. White once said: “The flood of money that gushes into politics today is a pollution of democracy.”Sources told The Heat tycoons and industry captains are willing to make huge donations to government leaders and heads of political parties for their campaigns, with the hope that they would be favourably treated when these people were appointed to powerful positions.When these candidates get elected, it would be payback time. The projects that are carried out by the candidates’ beneficiaries may get the nod, despite protests by the people. It is, however, difficult to prove such interference without disclosure of the names of campaign fund donors.Although most contributions given to candidates come mostly in the form of cash, there are different forms of favours they can pledge. Fund-raising dinners where everything is paid for by benefactors is one of them.Former MCA member and five-term Subang Jaya assemblyman Datuk Lee Hwa Beng tells The Heat that political funds can come from individuals as well as companies, mostly developers.“This is because developers are the ones who would be most affected by the outcome of an election. Hence, developers would usually give both sides of the political divide though the amount may vary,” says Lee, who lost in the 2008 general election.The retired politician says these ‘contributions’ would sometimes be offered voluntarily, or they would be approached at times by the political parties.“Businessmen with no self-interest would also give to the political party they support. Besides that, friends of the candidates would also lend their support,” says Lee.“These contributions would normally be given in cash, so that it would not be traced back to them. The money would be given directly to the candidate alone and not through a political party’s bank account.”Lee admits that based on his experience, most candidates from both sides of the political divide could actually make money from campaigning. The problem is, he says, no one keeps a check on the amount spent and if there is any money left, no one would be the wiser.“In the 2008 general election when the then state government gave us an allocation to contest, I actually had money left over and I returned it after I lost the election.“I do feel it is time we look into regulating this like how they do it in the United States. There is nothing wrong with people donating or contributing to election campaign funds, but the money must be declared. This would then be submitted to the Election Commission to show how the money is spent,” he says.PKR’s Yusmadi Yusoff and former one-term Balik Pulau member of parliament (MP) says that during the 2008 general election, he was given RM15,000 by the central party to campaign and that was all he used to win the election.“I did not source money from any individual, except that a businessman donated two boxes of mineral water for my supporters,” Yusmadi saysHe says sourcing of funds for election campaigns actually makes democracy more expensive. “I know parties like PAS and DAP are quite active in raising their funds during ceramah. They can raise quite a lot, particularly in the urban areas,” says Yusmadi.He says since the 2013 general election, his party’s treasurer at the central level appointed a campaign director for each constituency to monitor campaign donations.“The nexus between political finance, dynamics or leadership can be interpreted based on the local development of the area. For example in Balik Pulau, some development projects are still being carried out despite complaints by locals who claimed they were victimised through forced eviction,” he says.According to the Malaysian Corruption Barometer 2014 released by Transparency-International Malaysia (TI-M) recently, Malaysians ranked political parties as the most corrupt among six key institutions. The police scored second place, followed by public officials or civil servants, the judiciary, parliament or legislature, and business or private sector.TI-M called for more transparency in political financing expenditure for campaigning to curb corruption and stop money politics. It urged the government to regulate financing for all political parties where all forms of contributions and funding must be channelled to an official party account and not into political candidates’ personal bank accounts.DAP election strategist Dr Ong Kian Ming, who is also Serdang MP, says the proposal to regulate political finances would only be viable if there is a genuinely level playing field.“My fear is that this may be used as a tool to ‘scare’ people off from contributing to opposition parties, without controlling the flow of funds to the BN parties through official and non-official channels,” he says.“For example, legislation may be introduced to make it compulsory for political parties to disclose the identity of supporters who make donations above a certain amount but does not stop companies or individuals from giving to BN parties through non-official channels.”Ong says as far as DAP is concerned, the party’s election funds are obtained from supporters who attend ceramah and those who contribute to the party’s bank account.He says candidates also get donations directly from friends, family members and their supporters. He adds that he was not aware of donations from companies.“Some funds are given to the party through its official bank accounts while other funds are channelled to the party branch account to be used for individual candidates. The decision on which account to bank the contributions into is up to the individual supporter,” says Ong.The interdependence of party politics and business sectors – once dubbed as an “incestuous relationship” by veteran opposition politician Lim Kit Siang – is prevalent in low-income and developing nations, more so in Southeast Asia.In reality, political parties and their candidates need the political funds to reach out to voters and to ensure governance. To ban such donations to parties would leave them high and dry, incapable of running an effective campaign.The acceptable compromise would be for clear rules to be created to usher in an era of transparency, so that the “dark money” may be brought into the light. Big companies should donate because they support the party they think will do a good job of governing the country, not because they would get favours from it.

This article was first published in the June 21, 2014 issue of The Heat

For further reading see also: Aboo Talib, Kartini: The Political Parties in Malaysia, in: Sachsenröder, Wolfgang (ed.): Party Politics in Southeast Asia, Singapore 2014, available at Amazon, Barnes&Noble and other internet book distributors.