Dear friends,

This is my last post on this blog. After more than 400 posts and reaching a “biblical” age, I retire from Partyforum SEA and will focus on my new career path as a freelance writer and journalist.

Any younger political scientist may feel free to contribute fresh content. The blog will stay open for volunteers.

All the best and thanks to the readers,

Wolfgang Sachsenroeder

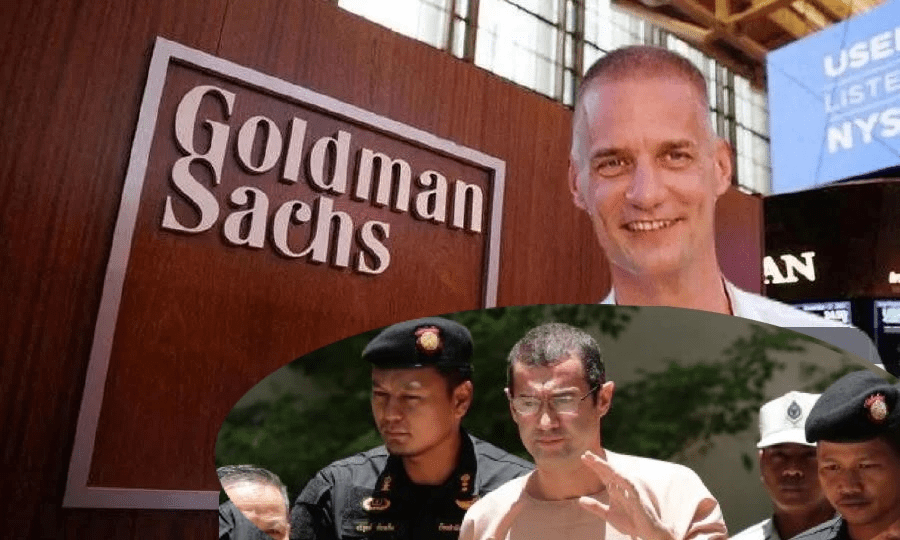

1MDB on the legal level but not ending in Malaysia yet

The latest developments and the bankers’ involvement. Must read!

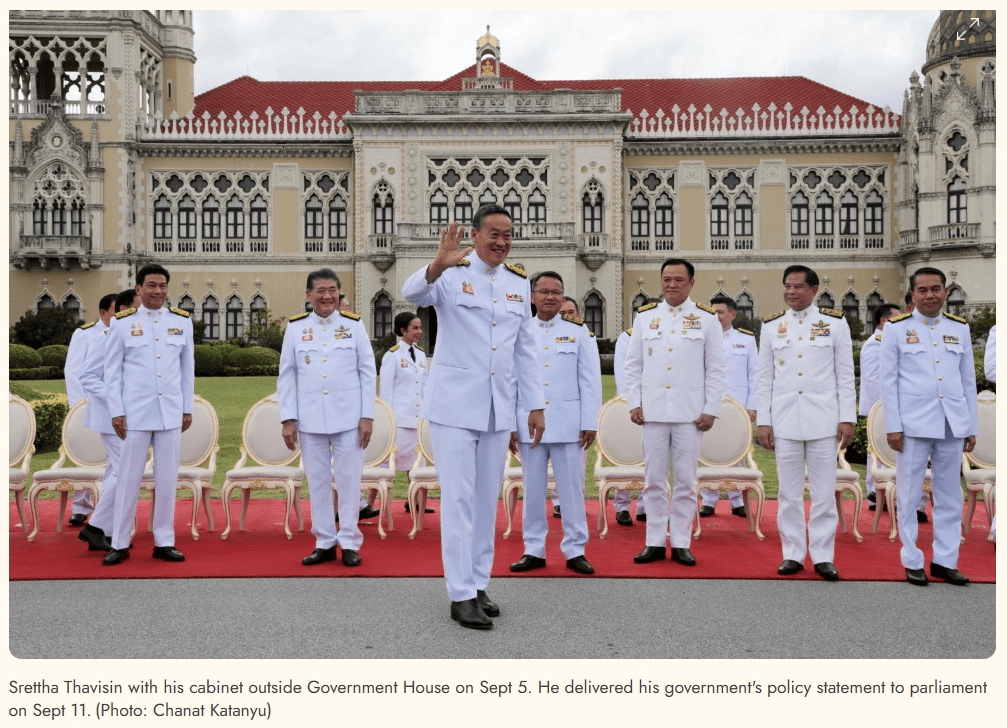

Thailand

Highly recommended for content and circumstances of the author…

Bangkok’s penchant for political pluralism has persisted. In the 2026 elections, this would see a popular and independent incumbent pitted against an up and rising opposition party.

https://fulcrum.sg/bangkok-politics-in-2025-beacon-of-thai-pluralism/

Social media in election campaigns: How it worked in Germany

How TikTok Helped the Far Left Surprise in Germany

Struggling a month ago, the Die Linke party surged into Parliament by riding a backlash against conservative immigration policy.

By Tatiana Firsova and Jim Tankersley New York Times

Reporting from Berlin

Feb. 24, 2025

Her fans call her Heidi. She is 36 years old. She talks a mile a minute. She has a tattoo of the Polish-German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg on her left arm and a million followers across TikTok and Instagram. She was relatively unknown in German politics until January, but as of Sunday, she’s a political force.

Heidi Reichinnek is the woman who led the surprise story of Germany’s parliamentary elections on Sunday: an almost overnight resurgence of Die Linke, which translates as “The Left.”

A month ago, Die Linke looked likely to miss the 5 percent voting cutoff needed for parties to earn seats in Germany’s Parliament, the Bundestag. On Sunday, it won nearly 9 percent of the vote and 64 seats in the Bundestag. It was one of only five parties to win multiple seats in the new Parliament, joining the Christian Democrats, the Social Democrats, the hard-right Alternative for Germany and the Green Party.

It was a remarkable comeback, powered by young voters, high prices, a backlash against conservative politicians, and a social-media-forward message that mixed celebration and defiance.

At a time when German politicians are moving to the right on issues like immigration, and when the Alternative for Germany, or AfD, doubled its vote share from four years ago, Ms. Reichinnek, the party’s co-leader in the Bundestag, and Die Linke succeeded by channeling outrage from liberal, young voters.

They pitched themselves as an aggressive check on a more conservative government, which will almost certainly be led by Friedrich Merz, a businessman who has led the Christian Democrats to take a harsher line on border security and migrants.

Mr. Merz’s ascent, and his decisions in the middle of a campaign that his party led from the start, appear to have helped Ms. Reichinnek. In January, after a deadly knife attack by an immigrant in Bavaria, Mr. Merz pushed the Parliament to vote on a set of migration restrictions that could only pass with votes from the AfD — breaking decades of prohibition in German politics against partnering with parties deemed extreme.

Many analysts trace Die Linke’s surge to Ms. Reichinnek’s furious — for the German Parliament, anyway — speech denouncing Mr. Merz and his measures.

“You just said that no one from your party is reaching out to the AfD!” she shouted, in a speech that has since racked up nearly seven million views on TikTok. “That’s right! They’ve been happily embracing each other for a long time already!”

In the month that followed, she called the AfD a fascist party and demanded that the Christian Democrats fire Mr. Merz. She proposed strengthening immigrants’ rights, increasing pensions and imposing stricter rent controls to help people struggling with postpandemic price increases across Germany.

She also called Die Linke the country’s last great firewall against the far right.

Die Linke coupled those calls with an aggressive social media outreach and party-like atmospheres at its rallies. It added more than 30,000 new members in the last month of the campaign, said Götz Lange, the party’s press officer.

In the campaign’s final week, Ms. Reichinnek traveled to the Berlin suburb of Treptow-Köpenick to talk to Ole Liebl, a queer influencer, about “techno and TikTok.” Afterward there was a party, with a DJ set, including a techno mix with the voice of a famed left leader in Germany, Gregor Gysi.

The venue, an old brewery, was bursting at the seams: Instead of the allowed 400 guests, around 1.200 people showed up. Most of them were techno lovers in black hoodies, people with multicolored hair and T-shirts with “antifa” slogans written on them. They mostly appeared to be in their early 20s.

There wasn’t enough space inside for everyone, so around 800 guests followed the event outside and downstairs, on a livestream. Wearing a rust red-colored sweater and jeans, Ms. Reichinnek appeared after a 30-minute delay, smiling and waving to the crowd.

“Thank you for being here,” she said. “It’s crazy, I don’t even want to know what it looks like down there. If you need help, try banging on the ceiling really loudly, we’ll know.”

The crowd roared.

On Election Day, Die Linke surprised analysts and appeared to snatch votes from the Greens and the Social Democrats, the party of the incumbent chancellor, Olaf Scholz, and got new voters to turn out. In Berlin’s central Mitte neighborhood, it won areas previously dominated by the Greens.

Founded in 2007 and descended from the former ruling party of East Germany, Die Linke had recently been better known for its failures than any success.

Its most well-known leader, Sahra Wagenknecht, quit the party to start her own — which blended some traditional left economic positions with a hard line on migration and an affinity for Russia.

That may have been a blessing, said Sven Leunig, a political scientist at the University of Jena, a public research university in Germany. Ms. Wagenknecht’s positions had split the party. “They were torn,” Mr. Leunig said, and voters did not like it.

The departure also allowed Die Linke to enlist new candidates and leaders. Other mainstream parties continued to push familiar faces and may have paid the price.

Daria Batalov, a 23-year-old nursing student from the central town of Hanau, said she was won over by Ms. Reichinnek’s TikTok videos. “They really spoke to me,” she said, adding, “And it was clear to me after a few videos that, OK, my vote is going to Die Linke.”

Analysts said Ms. Reichinnek and her party also benefited from a backlash to Mr. Merz’s migration measures, and from fears about the rise of the far right. “She had good luck,” said Uwe Jun, a political scientist at the University of Trier.

Her supporters called it something else: the rebirth of a movement. At Die Linke’s election-viewing party in Berlin, the crowd erupted into cheers when early exit polls flashed across the screen. Jan van Aken, a party leader, was greeted onstage with confetti.

“The Left lives,” he said.

Adam Sella contributed from Berlin and Sam Gurwitt from Hanau.

Jim Tankersley is the Berlin bureau chief for The Times, leading coverage of Germany, Austria and Switzerland. More about Jim Tankersley

The Problem with Party and Campaign Funding

Partyforumseasia: Running a political party is close to impossible without money. Many of the European parties of the 20th century could count on idealism and the support of their members. Reasonable membership fees were being collected by the treasurers of local branches where many members knew many of the co-members and the local leadership. In meetings they could discuss the party goals and develop leadership qualifications themselves and possibly rise in the hierarchy.

Today, that looks nostalgically outdated. Party machineries have grown into sophisticated entities with all the paraphernalia of a real business and turnovers of millions and sometimes billions. Campaigning is a big strategic challenge depending increasingly on state-of-the-art PR and dominance of the media, including the social ones. AI is contributing the icing sugar, and the top candidates develop pop star personas.

Membership fees are not more than a symbolic part of the overall budgets and mobilisation of dedicated members is getting obsolete.

Given these developments, the funding sources for our political parties deserve more attention and scrutiny by the public. Too often, if there are any rules for donations, the parties as well as the donors are not interested in openness and transparency. They prefer to hide the real amount of influence and their vested interests.

Here is an interesting case study from the United States:

Are we in a global democratic recession?

Today in Singapore’s Straits Times (13 December 2024, page 21)

Unfortunately, Partyforum Southeast Asia cannot help sharing the pessimism…

Super election year masks what’s really wrong with democracy

Election officials preparing to count votes during Japan’s general election on Oct 27. For democracy to hold its ground, the gap between what it promises and what it delivers cannot keep widening, says the writer.PHOTO: AFP

Record turnouts and robust competition may feel like a festival but, in many countries, democracy is not solving people’s problems. It’s in trouble.

By Bhavan Jaipragas, Deputy Opinion Editor

Are we in a global democratic recession? The numbers don’t seem to suggest that.

In 2024, the biggest election year in human history, with 3.7 billion people eligible to vote across 72 countries, experts noted strong turnout, vibrant political competition, and only limited success for disinformation campaigns.

The Economist, drawing on data from 27 countries, even noted a drop in election-related violence and protests compared with previous contests.

So, procedurally at least, democracy appears to be thriving. But let’s not be fooled by surface-level success.

Beneath this shiny exterior lies a troubling undercurrent of disillusionment, mistrust and dysfunction. This goes beyond doubts about the system itself – trust is eroding in the very people who run it.

In many places, politics no longer feels like actual governance – problems aren’t getting fixed today, and there’s little thought for the future.

In a Pew survey of 24 countries published in February (including India, Australia, Indonesia, Japan and South Korea, but excluding Singapore), a median of 74 per cent said elected officials in their country did not care what people like them thought.

The pollster said of the results: “One factor driving people’s dissatisfaction with the way democracy is functioning is the belief that politicians are out of touch and disconnected from the lives of ordinary citizens.”

Instead, as British commentator Stephen Bush put it recently on the affairs in his country, with politicians’ fixation on staying in power rather than day-to-day governing, it’s more like “staging theatrical set pieces between near-constant electoral clashes”.

This isn’t just a handful of isolated examples; it’s a pattern playing out across a good number of the world’s democracies. We’re seeing rising polarisation, the demonisation of rivals, power grabs that push the limits of executive authority, and a collapse of public trust. Peer beneath the surface, and you’ll find democracies once thought solid that are now flailing.

Asian fault lines

Take South Korea, front and centre after last week’s drama. President Yoon Suk Yeol’s abortive martial law declaration – a self-coup in all but name – tells you everything. To outmanoeuvre an obstructionist opposition, Mr Yoon flirted with wrecking the economy and national security. The message is clear: Crushing political foes tops any notion of the national good.

Japan wasn’t as theatrical in 2024, but one can argue it was just as myopic. Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, leading the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party in its current cycle of leadership churn, forced a snap election a year early. This calculated gamble, aimed at securing a fresh mandate, backfired, leaving his party without the majority it had held for 15 uninterrupted years. As The Straits Times’ Japan correspondent Walter Sim recently observed, Mr Ishiba is now on precarious footing heading into 2025. Long-term strategy? Off the table, it seems.

Consider also the Philippines. Instead of genuine policy debates, its rumbustious democracy boils down to dynastic feuds. The Marcos and Duterte clans are currently locked in ugly conflicts, even hinting at assassination. Under these conditions, one wonders why ordinary Filipinos would believe their elites care about anything other than holding on to power.

Even Western Europe – supposedly liberal democracy’s heartland – is not in a good place. France and Germany enter 2025 with governments toppled by budget feuds, proving they can’t compromise or level with voters about tough economic choices. All this as Europe braces itself for Donald Trump’s return to the White House, uncertain of American policy. Add Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine, and the leadership void in Paris and Berlin feels like a ticking time bomb.

Speaking of Trump, there’s the US – an obvious reference point for glaring democratic dysfunction. Re-electing a president who openly admires autocrats and once fuelled an insurrection attempt, and who now keeps the Republican Party firmly under his heel, lays democracy’s fragility bare.

Yes, it’s grim. But that’s the point. Regular elections and popular mandates might make democracy appear strong, but true democracy is revealed in its conduct – solving public problems and addressing the concerns and interests of ordinary citizens. To be clear, this isn’t a cheap shot at the democracies in place in these societies, or a suggestion that there’s a superior system to open, electoral contests for power. If anything, high turnout and waves of anti-incumbency in 2024 – across countless ballots – show just how fiercely people still believe in it.

The Democracy Perception Index, one of several surveys tracking how people view democracy, found in its 2024 poll that some 85 per cent of 63,000 respondents from 53 nations (including Singapore) viewed democracy as important, compared with 79 per cent in 2019 when the survey started.

And yet, paradoxically, even as voters line up at the polls, their faith in politicians and the system is crumbling.

Supply and demand factors

What’s behind this wobbling in the way democracy functions? To understand this, consider both “supply” and “demand” in electoral politics. Using the phraseology of Harvard University comparative politics professor Pippa Norris, much of the dysfunction comes from the “supply side” – how leaders and parties behave. Instead of mending disillusionment and restoring trust, many have deepened the divides.

Commentators have long noted that many leaders, buoyed by steady growth and easy credit, avoided tough economic decisions. That era is over, leaving today’s leaders to confront the problems their predecessors dodged.

Take Germany: Its fiscal shortfalls, energy security struggles, lenient emissions rules and pension woes all trace back to former chancellor Angela Merkel’s habit of deferring tough decisions – a tendency so pronounced it inspired the verb “Merkeln”. She leaned on a status quo that treated China as a reliable market and Russia as a steady energy supplier – until they weren’t. Now, Chancellor Olaf Scholz faces the fallout: a floundering electric vehicle sector, an ageing population, and an energy transition still in limbo. With elections looming, his centrist Social Democratic Party is squeezed by challengers on both the extreme left and right.

Not to single out Germany, but these supply-side political woes reflect a broader pattern plaguing many of the world’s oldest democracies. Short-termism appears everywhere: populist handouts and bloated social programmes that prove unsustainable, anti-immigration rhetoric that placates xenophobia but hobbles long-run growth, and tariffs slapped on foreign goods that might bolster short-term sentiment but sabotage long-term competitiveness. This pattern repeats across democracies. Mainstream parties – left, right or centre – keep chasing quick electoral gains while sacrificing enduring stability, leaving voters disillusioned and betrayed.

That anger clears the way for right-wing groups and other fresh faces who promise quick, easy answers. They tap into everyday worries – rising prices (blamed for 2024’s anti-incumbency wave), a shortage of homes, joblessness, and crime – invoking a simpler past when life seemed smoother. Desperate for solutions, people give them a chance. But tough problems don’t vanish just because someone claims they can fix them overnight. When these newcomers fail, disappointment runs even deeper. The cycle starts all over again, making it harder to have calm, sensible conversations about what to do next.

Still, blaming politicians alone is too easy. Democracy works both ways, and voters share responsibility.

Take France. Its recently sacked government tried to impose spending cuts and tax hikes to plug a huge deficit and mounting public debt. The far-left and far-right parties that oppose such measures ignored this economic reality but remain highly popular. This is despite an ageing population and rising security costs that will only strain public finances further. There’s little willingness to admit that budgets can’t be stretched indefinitely, or that someone eventually ends up footing the bill for generous social spending. The so-called chattering classes seldom draw attention to these uncomfortable truths.

As Financial Times columnist Janan Ganesh noted in 2022, lamenting similar “demand side” issues in Britain, voters are rarely assigned any blame. In his words, “there is something messianic about the notion that, if voters err, it is because of goings-on among one’s class at the commanding heights of society”.

These financial pressures aren’t going away, and many voters remain unwilling to acknowledge the necessary trade-offs. The outcome is a vicious circle: more heated rhetoric, deeper extremes and fewer workable solutions.

No quick fixes

Is there a quick fix to this democratic malaise? Of course not. But in recent days, as commentators reflected on just how close South Korea came to losing its democracy, a number of old proposals have resurfaced.

For starters – without sounding corny – voters need to adopt a “what can I do for my country” mindset. If you don’t like what you see, do something about it.

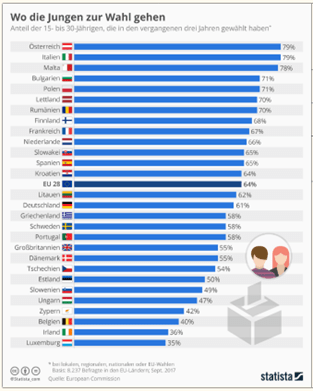

Political scientists have warned for decades about declining participation in political parties. In Europe, for instance, party membership has fallen sharply.

Disillusionment with traditional parties is part of the problem, but that creates a self-perpetuating cycle. Parties stay dominated by the same elites who seem out of touch, while citizens stay on the sidelines, leaving a vacuum that opportunists easily fill.

Another remedy: Voters should make more informed, sensible choices, and not be swayed by comforting fantasies. Don’t get bribed by handouts your country can’t afford. Don’t join calls to throw out foreigners and imagine that this will not hurt your economy. Easy to say, yes, but it still needs saying. The antidote is to stay informed, think long term, and not fixate on single-issue politics.

As for the political elite – the “supply side” in these places where affairs are especially dysfunctional – they don’t need more lectures. They know democracy is in trouble, and they’ve said as much. But acknowledging the problem and actually doing something about it are two different things.

Whether they mean what they say about changing their ways is another question.

One thing is clear: Procedural democracy still stands strong, as evidenced by this vast “festival of democracy” in 2024.

But for democracy to hold its ground, the gap between what it promises and what it delivers can’t keep widening. Both voters and leaders, the “demand” and “supply” sides of politics, have a part to play – if they don’t step up, democracy risks becoming exactly what its fiercest critics say it is: a noble idea that never works out in real life.

bhavan@sph.com.sg

The Beginning of the End of Election Campaigns?

Partyforumseasia: Are social media replacing old fashioned campaigning with posters, canvassing, rallies, and personal activities of party members? If yes, election campaigning could become much cheaper than the recent billion $$ presidential campaign in the U.S.

Here is an interesting case from Japan:

Japanese politician rides social media wave to polls win

Mr Motohiko Saito’s campaign for re-election cast him as an underdog reformist, among other things.

His stunning comeback after ouster from office rattles political, media establishments

Walter Sim, Japan Correspondent, Straits Times, Singapore, 26.11.2024

TOKYO Japan is reckoning with its first social media-influenced election of consequence, as a spectacular political comeback rattles traditional political and media establishments, while even being compared with Donald Trump’s victory in the US presidential election.

On Nov 17, Mr Motohiko Saito, 47, won a second term as the Governor of Hyogo prefecture, despite having been ousted just weeks earlier in a unanimous no-confidence motion across the political divide in the local assembly.

He had been accused of “power harassment” – or abuse of authority – as well as bullying that led to the suicide of a whistleblower against his administration, among other things.

Japanese media was quick to write him off, and his career seemed dead in the water. Photographs online after his ousting showed a forlorn figure standing alone at a train station, with passers-by giving him the cold shoulder.

But social media helped in Mr Saito’s rehabilitation, resulting in a stunning re-election over six other candidates to govern the western prefecture of 5.3 million people that borders Osaka and is known for the cities of Kobe and Himeji.

Turnout, at 55.65 per cent, was substantially higher than the 41.1 per cent in 2021.

This came as mainstream media outlets in Japan, which like titles elsewhere in the world suffering from a decline in readership, were perceived to be biased in their reporting about Mr Saito.

His campaign tapped into these sentiments to criticise traditional establishments, while also speaking directly to voters who were dissatisfied with the status quo.

“No one thought this would happen a few weeks ago,” political scientist Ko Maeda of the University of North Texas told The Straits Times.

“Either the media reports were wrong, or Saito’s support increased greatly in the last few days of the campaign. Or maybe both.”

The result has triggered a wave of soul-searching. On Nov 18, a headline in the Sankei newspaper pondered: “Is Saito’s re-election a defeat for mass media and a victory for social media?”

The introspective piece compared Mr Saito to US President-elect Trump in his victory against a groundswell of resentment, adding that public distrust of mainstream media that had been harsh with its condemnation of Mr Saito had worked to his advantage.

Both men also emphasised reforms in their crusade against the status quo.

Among the commentators who have weighed in on the result is mountaineer Ken Noguchi, who wrote on X: “It seems like the Trump wave has surged across the Pacific Ocean. Either way, the era in which mass media equals public opinion is over.”

However, Mr Noguchi, whose comments about Mr Saito have been widely picked up by the Japanese media, added: “As distrust of mainstream media grows, I also feel an acute sense of danger that social media, which often has unreliable information, will take centre stage.”

Mr Nobuo Inaba, chairman of public broadcaster NHK, told a news conference on Nov 20: “How can the media provide appropriate information for people to make their voting decisions? We need to seriously consider what our role as a public broadcaster is in election reporting.”

Mr Saito won 1.11 million votes, or 45.2 per cent of the total, handily defeating hot favourite Kazumi Inamura, 52, the former mayor of Amagasaki city, who won about 970,000 votes.

Ms Inamura, who won the backing of 22 out of 29 city mayors in Hyogo, echoed mainstream media in her criticism of Mr Saito for his alleged authoritarian tendencies.

But Mr Saito’s campaign, supported by his former classmates and hundreds of volunteers recruited through social media, cast him as an underdog reformist and a hero who went too far in upsetting entrenched vested interests.

“Was the media’s reporting truly accurate? Were some prefectural assembly members only interested in political manoeuvring?” Mr Saito said in a stump speech during a campaign in which he repeatedly stressed his innocence.

“What is the truth? And what is truly the best for the prefecture?”

Over street speeches and live streams on social media, he also touted his track record in his three years as governor, during which he reduced his wages by 30 per cent and made prefectural universities free of charge, while weaving in personal stories from his upbringing and school days.

Mr Saito said after his victory: “I’ve never really liked social media because it is a hotbed of harsh comments, but I’ve come to see its positive side in how it reaches a lot of people and spreads support.”

Doshisha University political scientist Toru Yoshida told ST: “This election reflects how traditional parties have completely lost the grip on independent voters, and are very much behind in new ways of mobilising them.”

He added that analyses have shown that the most significant difference between Mr Saito’s and Ms Inamura’s voters is their degree of trust in traditional media.

Still, in a sign of how social media may be unfairly weaponised, Ms Inamura’s campaign lodged a report with the Hyogo Prefectural Police on Nov 22 over the freezing of her social media accounts during the election period, purportedly because large numbers of people made false reports to platform operators.

Mr Saito’s victory comes on the heels of the political ascent of Mr Shinji Ishimaru, 42, who had little name recognition but rode the wave of social media to place second in the Tokyo governor race in July, winning more votes than the much higher-profile opposition candidate Renho, who goes by one name.

Mr Ishimaru said on Nov 12 that he plans to establish a new regional party ahead of the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election in July 2025.

Nationwide, the Democratic Party For The People not only quadrupled its presence in Parliament in a general election in October, but is now the most favoured party among under-40s given its social media presence, according to various media polls.

“Traditional media will probably try to maintain public support and trust by asserting that their reports are more trustworthy than what people see in social media,” Dr Maeda said. “But I don’t know if the power of social media will ever become smaller from here on.”

Dr Yoshida, meanwhile, said that although traditional media is shocked by the Hyogo outcome, its approach to news reporting “will not change in a day, given the need for reforms”.

waltsim@sph.com.sg

After the Third Wave of Democratization the Struggle between Democracy and Authoritarianism is back…also in the USA

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/democracy-without-america-trump-larry-diamond?utm

Larry Diamond was one of the leading theorists during the Third Wave optimism. In the meantime, the old catchword “irreversible” sounds outdated. Unfortunately!

At least no more triumphalism…

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/1997-09-01/has-democracy-future?utm

| As Americans head to the polls in this year’s U.S. presidential election, many across the political spectrum believe that the future of democracy is at stake. Voters around the country have expressed grievances over the state of the U.S. political system and its failure to adequately address issues such as inflation, inequality, and global instability. Writing in 1997, the eminent historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. presaged such discontent. Despite the triumphalism of the West after the fall of the Soviet Union, he warned, democracy in the United States and elsewhere would confront major challenges in the years ahead. In the twentieth century, “the political, economic, and moral failures of democracy had handed the initiative to totalitarianism,” he wrote. “Something like this could happen again.” Should liberal democracy fail “to construct a humane, prosperous, and peaceful world, it will invite the rise of alternative creeds apt to be based, like fascism and communism, on flight from freedom and surrender to authority.” Schlesinger emphasized that humanity’s experiment with democracy was brand new in the grand scheme: “a mere flash in the long vistas of recorded history.” Over the next century, it would be put to the test; democracy “must manage the pressures of race, of technology, and of capitalism, and it must cope with the spiritual frustrations and yearnings generated in the vast anonymity of global society.” Even in the face of such challenges, he argued, “the great strength of democracy is its capacity for self-correction.” Still, “even the greatest of democratic leaders lack the talent to cajole violent, retrograde, and intractable humankind into utopia.” |

Democracy in Decline

Partyforumseasia: The Third Wave of Democratization is history, optimism is more and more being replaced by pessimism. International IDEA is explaining it with carefully collected facts and research. Their report

The Global State of Democracy 2024

Strengthening the Legitimacy of Elections in a Time of Radical Uncertainty

is a must read for everybody in politics or concerned with one’s own politics at home.

Key findings

1. Despite the many threats to elections and the declines found in many countries, elections retain their promise as a mechanism for ensuring popular control over decision makers and decision making. Incumbent parties have lost presidential elections and parliamentary majorities in many highly watched elections in 2023 and 2024.

2. In an election super-cycle year in which approximately 3 billion people will go to the polls, one in three¹ will vote in countries where the quality of elections is significantly worse than it was five years ago.

3. Electoral outcomes are disputed relatively frequently. Between 2020 and 2024, in almost one in five elections a losing candidate or party rejected the electoral outcome. Elections are being decided by court appeals at almost the same rate.

4. The global rate of electoral participation has declined as elections have become increasingly disputed, with the global average for electoral turnout declining from 65.2 per cent to 55.5 per cent over the past 15 years.

5. Countries experiencing net declines in democratic performance far outnumber those with advances. About one in four countries is moving forward (on balance), while four out of every nine are worse off.

6. Declines have been most concentrated in Representation (Credible Elections and Effective Parliament) and Rights (Economic Equality, Freedom of Expression and Freedom of the Press).

7. In addition to declines in weaker contexts, democratically high-performing countries in all regions have suffered significant deterioration, especially in Europe and the Americas.

8. While substantial progress has been made in improving electoral administration, disputes about the credibility of elections deal mainly with irregularities at the point of voting and vote counting.

The whole report is available here: The Global State of Democracy 2024 Report (GSoD): Strengthening the Legitimacy of Elections in a Time of Radical Uncertainty.

NB: The country ranking, ending with the United Arab Emirates and Yemen at the bottom and starting with Germany und Uruguay on top is open to debate. As an old German living abroad but following the news, I have my doubts…

From Mega-Project to Micro-Mega-Project?

The Rear-Guard Battle of the Thai Establishment?

Partyforumseasia: Banning a popular party is a sensitive political move. In this special case it may be a move backwards and betray the structural and historical weakness of the Monarcho-Military Complex of Thailand. “Smooth as silk”, as the famous tourism logo of the kingdom wants to make us believe, would look different. And the obvious democratic aspirations of Thailand’s younger gemerations show that the ban might be another strategic mistake of the old order. As the French writer Victor Hugo said: “An invasion of armies can be resisted, but not an idea whose time has come.”

Yesterday’s comment in the AsiaTimes describes the details:

Move Forward ban a lurch backward for ThailandCourt dissolution of election-winning Move Forward pulls the monarchy into Thailand’s political fray in an unprecedented way.

Link: https://asiatimes.com/2024/08/move-forward-ban-a-lurch-backward-for-thailand/?mc_cid=372a2ab3c8&mc_eid=fedd701c2c

Free Speech in Asia

Asians Believe They Should Be Able to Criticize Governments

By Katharina Buchholz,Jul 22, 2024

A Pew Research Center survey of nine Asian countries shows that a majority of people in the region believe that free speech is important. Between 83 percent in South Korea and 55 percent in Singapore said that they believed that people should be able to publicly criticize their governments.

Also high on the list of proponents were Hong Kong and Taiwan, where upwards of 80 percent of people agreed with the sentiment. While having self-governed and gained independent democratic structures for a long time, both places have a complicated relationship with China, which regained control of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom in 1997 while also claiming Taiwan.

Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand are also highly in favor of free speech, while Japanese respondents were more timid. The idea was less widespread in Malaysia and Singapore, two countries known for their sometimes draconian laws which caused them to score low on some areas of the world press freedom index. While all countries in the survey were rated at least partially free on the World Freedom Index, Pew did not pose the question in its survey countries Vietnam and Cambodia, which are rated “not free”.

Trump or Biden? What matters in TV-duels.

“Many voters respond to style more than substance. The well-delivered quip lingers longer than the litany of facts, and the visual often trumps the verbal”.

What most of us instinctively know, clarified here by a long-term observer of US election debates. Analyzing a debate point by point and fact-checking are useful but do not gauge the reactions of the voters.

If you’re a typical American voter in any party, allow me to let you in on a little secret: What matters most to you in a presidential debate probably isn’t the same thing that gets the most attention from the candidates, the campaigns and their allies in the immediate aftermath of those big televised showdowns.

I’ve learned this from studying American reactions to almost every general election presidential debate since 1992. I’ve sat with small groups of voters selected from pools of thousands of undecided voters nationally, watching more than two dozen presidential and vice-presidential debates in real time, and it still amazes me that minuscule moments, verbal miscues and misremembering little details can matter so much in the spin room and to partisan pundits afterward. Yet those things often have little to no discernible impact on the opinions of many people watching at home.

To be fair, some of the debates I watched with voters, like Bill Clinton and Bob Dole’s in 1996, had no major impact on the electorate’s mood. Others — like the three-way town hall debate with Mr. Clinton, George H.W. Bush and Ross Perot in 1992 and the first George W. Bush-Al Gore debate in 2000 and the three Donald Trump-Hillary Clinton collisions — arguably changed history.

As the first scheduled debate between President Biden and Mr. Trump unfolds this Thursday, the key moments that will have the greatest impact on the remaining undecided voters are those in which the candidates attack each other in defining ways or undermine the political case that each wants to present to Americans. Viewers will quickly decide whether the accusations are fair and the responses effective. From Ronald Reagan’s “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” in 1980 to Barack Obama emphasizing hope and change in 2008 to Mr. Trump telling Mrs. Clinton in 2016 that she would “be in jail” if he won, I think those key debate moments made a meaningful difference in shaping the opinions of undecided or wavering voters who related to what they heard; I certainly saw it in my focus groups and public opinion research. These moments mattered more than any candidate flub or gaffe.

And sometimes it’s a feeling rather than a specific moment that matters. The best examples are John Kerry in the 2004 debates and John McCain in the 2008 debates: Both men were good public servants with impressive personal narratives, and neither said anything wrong in their debates. But neither did they say anything especially or memorably right. Many voters were left feeling unmoved and therefore unaffected.

At the risk of offending every high school debate coach in America, many voters respond to style more than substance. The well-delivered quip lingers longer than the litany of facts, and the visual often trumps the verbal. It’s not just that the electorate tends to be drawn more to younger and more attractive candidates (like Mr. Obama, Mr. Clinton and John F. Kennedy) or to those with more commanding stage presence (which Mr. Reagan had over Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale, and George H.W. Bush had over Michael Dukakis). While the 2016 and 2020 debates featuring Mr. Trump certainly upended our collective expectations about what exactly is presidential, listening to the voters describe each debate and their gut impressions of the candidates is more instructive about the eventual election winner than getting swept up in spin and punditry.

Perhaps the single best example of divergence between voter opinions and the views of politicos and pundits was the 1992 town hall debate. In the immediate aftermath, Mr. Bush was pilloried by the professional class for checking his watch during the debate — a moment that was completely missed by my focus group of American voters. To them, the biggest takeaways were Mr. Bush’s inability to explain what the federal deficit meant to him and then Mr. Clinton’s Oscar-worthy performance as he deftly stood up from his stool and approached an audience member with empathy and compassion, her head nodding in agreement with him throughout the encounter.

A similar misreading of a debate performance came from the first debate between George W. Bush and Mr. Gore, when a number of political analysts praised Mr. Gore for his command of the facts and intricacies of presidential decision making, while much of America seemed pleasantly surprised (shocked, actually) that Mr. Bush was able to string together complete sentences that were competent, coherent and compelling. Voters in my focus group were impressed with Mr. Bush’s comfort and command of the debate stage and disappointed with Mr. Gore’s stiffness and annoyed with what they saw as his dismissiveness toward his opponent.

In almost every presidential debate since 1992, voter expectations of a candidate’s performance also played a major role in determining perceptions of success and failure. Many had low expectations of Mr. Bush in 2000 and Mr. Trump in 2016 (and Mr. Biden now). The fact that they didn’t completely flop led at least some voters to see these candidates as surprisingly successful in the debates.

Many election observers believe that the incumbents start with some advantage because they have national debate experience and a command of governing. In Thursday’s case, both men have that experience, so voters will be looking at other factors — probably related to energy, sharpness and how they come across. While the specific circumstances were different, I think about the shock I felt watching Mr. Obama and Mitt Romney in their first debate in 2012. The widely held assumption was that Mr. Obama’s grace and charm would easily overwhelm Mr. Romney’s stiff and businesslike approach. But Mr. Obama was so chill in his approach that he came across as cold and uncaring to many voters. His performance was criticized by my focus group for lacking his customary passion and conviction — a surprising evaluation from a politician so popular for those qualities.

But here’s the surprising twist: In time, many voters came to see that first encounter with more nuance than that instant reaction suggested. In my Election Day 2012 focus groups, voters said they were left thinking that Mr. Obama truly understood them and their concerns but that he had no answers or solutions to their problems. Conversely, they felt that Mr. Romney had the better solutions to the challenges they faced but that he just didn’t fully understand their problems. Yes, policy solutions definitely matter in presidential debates. But personality, relatability and dignity matter more.

And it’s not just the candidate’s personal performance that leaves an impression. Sometimes forces that are less visible, like the debate rules, play a major role in determining the outcome. The length of time given to respond to questions from the moderator can reward or punish candidates, depending on their individual styles and ability to communicate succinctly. Nothing draws the ire of the average voter more than candidates speaking beyond their allotted time, my focus groups have shown. While most professional debate observers ignore candidates who run long, voters punish them mercilessly. It was a major reason many undecided voters turned so strongly against Mr. Trump after his undisciplined performance in the first debate in 2020.

That debate, the most consequential one in memory, was one in which many voters and political experts drew roughly the same conclusions. Mr. Trump entered the debate trailing Mr. Biden by just a couple of percentage points, but his questionable strategy to insult, badger and bully Mr. Biden was received so badly by the women in my focus group that they were as harsh about Mr. Trump as he was to Mr. Biden.

In contrast, there was one moment in the Trump-Clinton debates when voter opinion really struck me. It was Mr. Trump’s offhand comment that Mrs. Clinton belonged in jail. Many pundits and political experts hated it. My focus group loved it. For them, it was accountability in action for someone as important as her, a former secretary of state. To be sure, many political experts zeroed in on the moment as a striking instance of a presidential nominee threatening to weaponize the justice system against his opponent. But I think what they missed was a yearning among some voters to see a senior official held to account and not let off the hook by a system seen as protecting insiders.

This week brings us potentially one of the most consequential debates since Mr. Kennedy and Richard Nixon’s. The expectations are already high for Mr. Trump, who dared Mr. Biden to debate at any time or place of his choosing. It is quite possible that Mr. Trump will regret issuing such a public challenge, and Mr. Biden may regret accepting the offer.

To shape and sway voter opinion, the two opponents need to use the debate to do what Mr. Reagan, Mr. Obama and Mr. Trump did at their best: Crystallize the stakes of the race and the choice in November with a single memorable line that speaks to the feelings, instincts and perhaps even the fears of so many voters about America today.

Given that viewers are conditioned to see the 2024 debates as a mix of television entertainment and a war for America’s future, they will want to see passion, energy and even anger in service to the interests of the country. A self-controlled Mr. Trump or an adult Mr. Biden won’t be remembered, just as Mr. Kerry and Mr. McCain weren’t remembered. So much is at stake that both candidates need to let loose to make a lasting impression but not in a way that may alienate key groups like suburban women and swing voters.

In the end, it’s not the facts, the policies or even the one-upmanship that Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump offer in the debate that matters. It’s how they make voters feel.

Politics is all about influence

Successful and clever parties use any new channel for spreading their message. Singapore’s People’s Action Party (PAP) is one of the most successful political parties in the region and always open to new ways of connecting with the voters. With a new Prime Minister and elections round the corner, recruiting INFLUENCERS from outside the party ranks looks like a clever move.

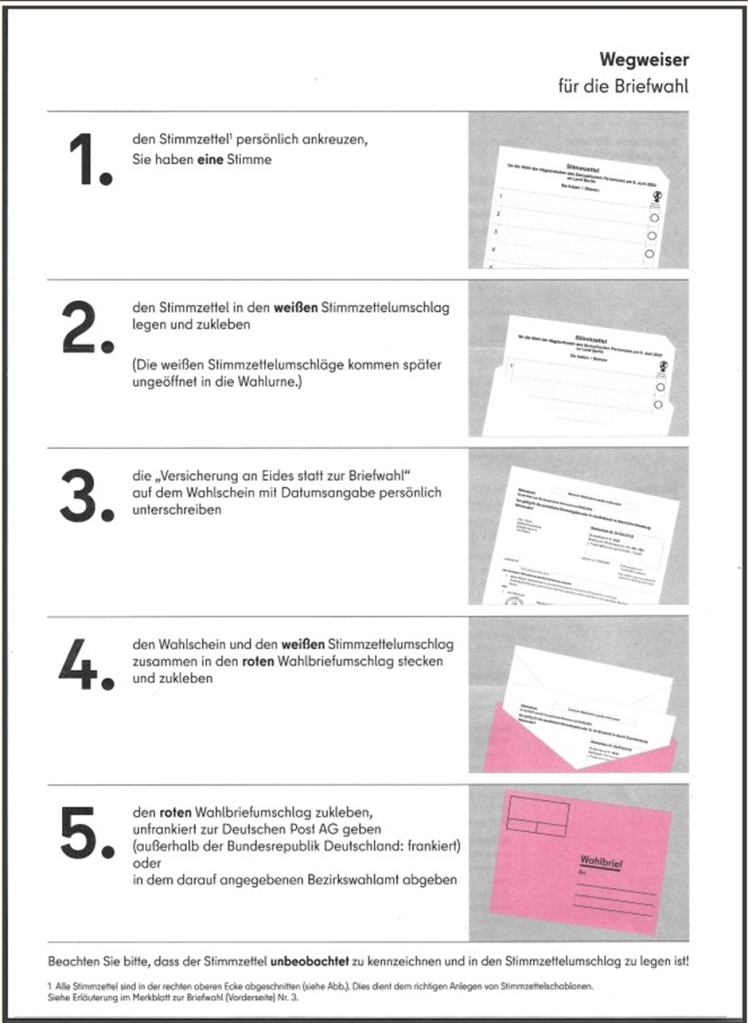

The European Parliament Election in Germany

Earlier this week, I received my ballot paper for the European Parliament Election, marked it immediately and rushed to the next post office to send it back to Berlin. Since this was my last registered residence in Germany, from where I moved to Singapore 16 years ago, the city administration in a suburb of the German capital is still responsible for my participation. And the deadline is looming, the election is on 9 June. For me the European Union is important, a dream come true during my lifetime. In my student days, my first membership after the Boy Scouts was with the “Young European Federalists”, and together with my parents, I was active in the Franco-German twin city movement. I was sad about the Brexit and sadder about the ongoing debates about other “-exits”.

In the ASEAN-debates over the last decades, the comparison with the EU was ubiquitous, often with a whiff of regret that ASEAN was not yet as far as the EU. Sure, ASEAN has no Parliament and no governmental institution like the powerful EU Commission which can make important political decisions binding the legislation of the member states. Just as an interesting example, look at the ban of combustion engines in motorcars by 2035 and the controversies it has created in the car industry.

At least for the average voter in Germany, the understanding of the role and decisions of the EU Parliament is limited. In the last election in 2019, the overall voter turnout was 50.6 %, the highest in twenty years, in Germany with 61 per cent even higher. This time, the very open party registration system in Germany does not make it more transparent or more attractive for the voters. The ballot paper is eighty centimetres long and lists 34 parties. While on the national level the ruling coalition between Social Democrats, Greens, and Liberals is increasingly unpopular, the main opposition Cristian Democratic Union joins the coalition in its fight against the more Right-wing Alternative for Germany. But probably many German voters will be surprised about the multitude of fringe parties they find on the ballot paper. If party systems all over Europa are more and more fragmented, with a trend toward the right because of the dramatic increase of immigration from Middle Eastern and African countries, 34 parties in Germany alone are somewhat strange.

Some curious fringe parties competing for a seat in the EU parliament, very probably have not much of a realistic chance. Either the five per cent threshold of all valid votes nor winning a direct mandate should be feasible for them, though some of the candidates on the list are quite prominent on the federal level in Germany. For many years, a certain type of political veterans has been “promoted” to Brussels, a parliament with limited powers of legislation. The right to initiate legislation lies with the commission and not with the EU Parliament, but the income of the MPs and the lifestyle in Brussels are attractive enough.

From the 80 cm long ballot paper below, parties 1 (The Greens), 2 (Christian Democratic Union), 3 (Social Democratic Party), 4 (The Left), 5 (Alternative for Germany), and 7 (Free Democratic Party) are established mainstream parties, the Social Democrats even with a 150-year history. The Alternative for Germany, as a right-wing party, is being attacked by all the others and the media. New on the scene is 28 (Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht) named after its leader, an outspoken younger politician who is omnipresent in talk shows and married to a Social Democratic veteran. As a registered party since only a couple of months, 28 is getting seven per cent in the polls, while The Left and the Liberal Free Democrats are struggling for survival above the five per cent threshold.

Surprisingly, socialist and communist tendencies have survived in Germany with the German Communist Party (20), Marxist-Leninist Party (23), and the Socialist Equality Party – 4th International (24).

With the environmental protection high on the government agenda via the Green Party in the ruling coalition, more groups are competing for Europe: The Ecological Democratic Party (13), Climate List Germany (30), and Last Generation (31) a grassroots group famous for street and airport blockades by gluing themselves to the streets.

The Action Party for Animal Welfare (15), Human World – Happiness for All (21), or the Party for Change, Vegetarians and Vegans (34) are the more exotic ones. But in an era where conservative world views and attitudes are uncool and being replaced by new and colourful lifestyles and social innovations, the list reflects the country’s transformations.

What reminds more of the old and bureaucratic Germany is the instruction leaflet for the postal vote procedure – at the end of this post after the ballot paper. The last instruction says that the voter should mark the ballot paper discreetly, without being observed by others, the secrecy of ballot principle.

How to Convince Voters in Confusing Party Landscapes

Fragmented Party Systems

In most of the so-called mature democracies the party systems are increasingly fragmented. Britain and the U.S. are an exception, mainly due to the First-Past-The-Post election system in Britain and presumably due to the sky-high campaign costs in the U.S. which discourage the formation and rise of new parties. In Europe the traditional party landscapes, if they are still visible, are falling apart at a fast rate. After WWII, Germany wanted to build a model democracy. One of the results was the ease of establishing and registering a new party, including the right (!) to get a downpayment for campaign cost reimbursement even before an election. So far so fair, but as an unintended result, there were new parties without a realistic potential, even as small coalition partners. In the last Federal Election in 2021 there were parties like “Free Voters” (vote share 2.4%), “The Animal Welfare Party (1.5%), “Pirate Party” (.4%), “Christians for Germany” (.1%), “Vegan Party” (.1%), and many others without votes. The threshold for entering the Bundestag is 5%. Combined with the decline of the old ideological parties, namely Social and Christian Democrats and Liberals, the European party systems show a tendency to splinter and make coalition building increasingly difficult.

Splinter Parties in Southeast Asia

In many countries in Southeast Asia, the party landscapes resemble the European ones in terms of complexity and lack of ideological differentiation. Highly visible, popular, or towering leadership figures may make up for the deficits, at least for a while, sometimes even for decades. But today it is more urgent than ever to convince and win over new voters. Since the era of “safe vote banks” seems to be over, it is even more important for the parties to come up with a convincing program and attractive leaders. But most of all, they should have a strategic concept of how to define the type of voters they can hope to convince. This is why their campaign plans need to focus on who can be convinced and how!

For concepts of “selling points” and “selling techniques” there is more than enough literature available. Voter’s opinions can change and can be changed, even to the opposite conviction if done the right way. Here is a link to the first example of a toolbox:

How Political Opinions Change | Scientific American

“In a recent experiment, we showed it is possible to trick people into changing their political views. In fact, we could get some people to adopt opinions that were directly opposite of their original ones. Our findings imply that we should rethink some of the ways we think about our own attitudes, and how they relate to the currently polarized political climate. When it comes to the actual political attitudes we hold, we are considerably more flexible than we think.” And so are voters…

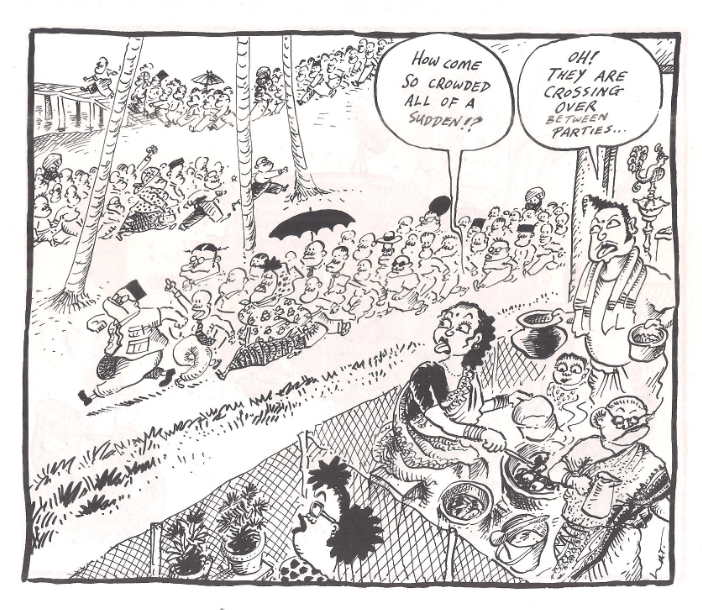

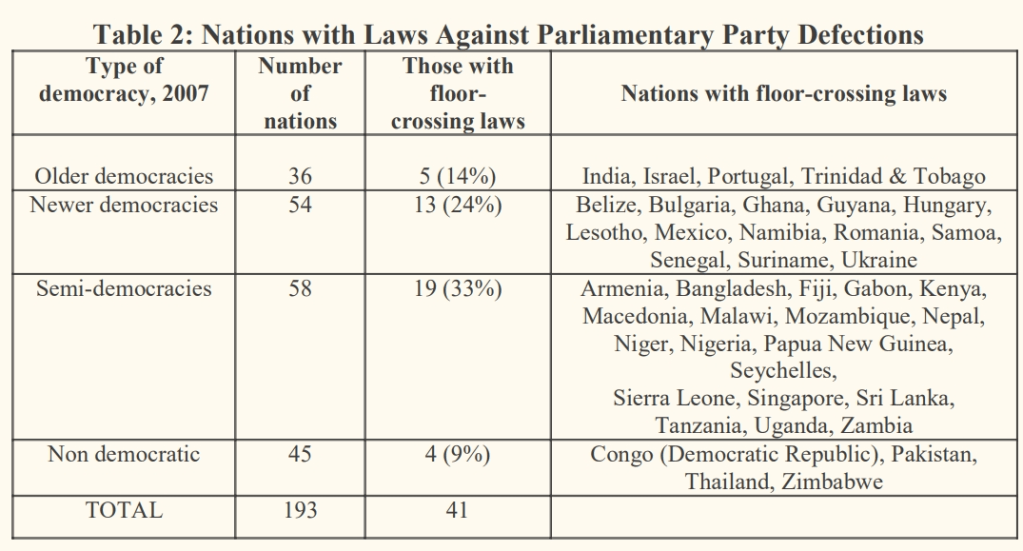

Is Party Hopping a Breach of Faith?

“Whenever a legislator elected on a party ticket or as an independent changes his party affiliation or joins a party, he commits a breach of faith. In most elections, party identity has more influence on the minds of the electorate than the personal prestige of the candidate. In fairness to the electorate, a defector should be made to seek a fresh mandate from the people.”

Kamath, P. M. (1985) “Politics of Defection in India in the 1980s,” Asian Survey, Vol. 25, No. 10, (October), 1039-1054.

Cartoon by Lat, Malaysia, 1980s

What Prof Kamath, a political scientist at the University of Mumbai, called a breach of faith, carries many negative names on the side of the “giving” or “losing” party, something between defection and treason or more. The “receiving” party, of course, sees it in a positive light, and may call it a courageous move, a plunge of belief, a trusting jump, or a decision of conscience. The single party hopper, though, as warmly as he or she may be welcomed in the new party will never be fully trusted. Converts are often more eagerly faithful than the other group members, and that is not too welcome as well.

Since party hopping has been widespread in Southeast Asia, regulated in some countries and often being discussed for tougher regulation in others, we don’t want to discuss the pros and cons here in detail.

For a good introduction into the party hopping topic, we recommend the analysis by Kenneth Janda, Northwest University, Illinois. The paper is from 2009 and offers a good comparative overview. For Southeast Asia, a couple of updates are necessary.

Link: wp0209 (leidenuniv.nl)

For a better understanding of politics in the region, the second sentence in the quotation above is at least similarly important, maybe even more:

“In most elections, party identity has more influence on the minds of the electorate than the personal prestige of the candidate.”

Partyforumseasia thinks that this is debatable and will continue to look into the issue. Contributions are welcome.

Party Funding in Malaysia and the UK

Irregular practices in the United Kingdom and other countries are no excuse!

Partyforumseasia: The old Romans had a couple of expressions for a basic social strategy which is common until today: “Do ut des” (I give you something so that you give me something back), “quid pro quo” (this for that), or “manus manum lavat” (one hand washes the other). The more popular modern expression in English is “palm greasing” which sounds much nicer than bribery, while the latter is widespread in East and West despite all attempts to fight political corruption.

In the case of party politics in Southeast Asia, the dilemma is that membership and membership fees are not common. Basic funding by members is practically unknown, unlike in Europe, where the traditional parties can still count on contributing members. Meanwhile, election campaigns are getting more expensive year on year, and suitable PR-companies and their helpers have to be paid in cash. Like in the U.S., rich donors help the parties, or more dubious in Southeast Asia, political parties can be bought by rich donors who, of course, expect a return on their investment. “Do ut des…”

These practices are not part of the democratic textbooks but may be stepping stones for a cleaner future with more concern for the voters and the interests of the countries.

Recommended reading, especially for Malaysians:

Party Funding Scandals – UK vs Malaysia (Sarawak Report)

The Conservative party’s biggest donor told colleagues that looking at Diane Abbott makes you “want to hate all black women” and said the MP “should be shot”, the Guardian can reveal.

Frank Hester, who has given £10m to the Tories in the past year, said in the meeting that he did not hate all black women. But he said that seeing Abbott, who is Britain’s longest-serving black MP, on TV meant “you just want to hate all black women because she’s there”….

… Hester, a businessman from West Yorkshire, runs a healthcare technology firm, the Phoenix Partnership (TPP), which has been paid more than £400m by the NHS and other government bodies since 2016, primarily to look after 60m UK medical records. He has profited from £135m of contracts with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) in less than four years.

Hester gave £5m to the Conservatives in May 2023 and announced this month a further £5m donation, which had been accepted by the party from his company in November last year. With months to go before the next general election, a party spokesperson confirmed he was now its “biggest ever donor”.

Source: UK Guardian

Our comment

Obnoxious views aside, the emergence of Mr Hester as the largest ever donor to the Conservatives in the UK is reminiscent of much that SR has criticised in Malaysia.

Thankfully for electors in Britain, there are levels of transparency that make matters of such blatant concern more accessible for journalists to draw to public attention.

However, this does not negate the need to confront an apparent perception of over-inflated public contracts being recirculated to the party of government that presided over the issuance of those very contracts. That’s the sort of thing whispered for years in Malaysia.

According to the Guardian, Mr Hester’s wealth has derived from the enormous profits obtained by his company from contracts to supply software services to the publicly funded National Health Service.

Latest recored results show the Phoenix Partnership (Leeds), had a turnover of £75m, with profit before tax of £47m in the year to March 2022.

As the owner, Hester received dividends during the year of £10m on top of a salary of £515,000 which he pays himself as the director.

If Mr Hester is making such enormous margins from these public contracts the immediate concern is that they would appear to be over-inflated. Competitors could surely have been found to perform the same work cheaper.

There is also a potential danger this flamboyant and opinionated businessman may have concluded that generosity towards the ruling party would secure further lucrative work.

Either way, there is a clear reform required to preclude companies in receipt of government contracts, or their owners, from making donations to the party whose ministers signed off on them for at least the duration of that parliament or contract.

If £10 million of public money is to be circled back into party political donations, the money should at least be divided amongst all citizens equally to contribute to the party of their choice: not funnelled through one entity which has just benefitted from an overpriced contract.

After all, this is public money and the public have a right to decide through a majority who gets the most support.

Malaysia is starting its clean up from an even more questionable state of affairs and in order to do so major steps towards transparency, which has regressed in recent years, should be addressed.

The CIDB website, which registers all awards of public contracts and has been made deliberately inaccessible since 2015, ought to be restored to public scrutiny as a first crucial step.

For now, newspapers cannot even report on the sort of matters the Guardian has just shocked its readers within Britain.

11 Mar 2024 Link: Party Funding Scandals – UK vs Malaysia | Sarawak Report

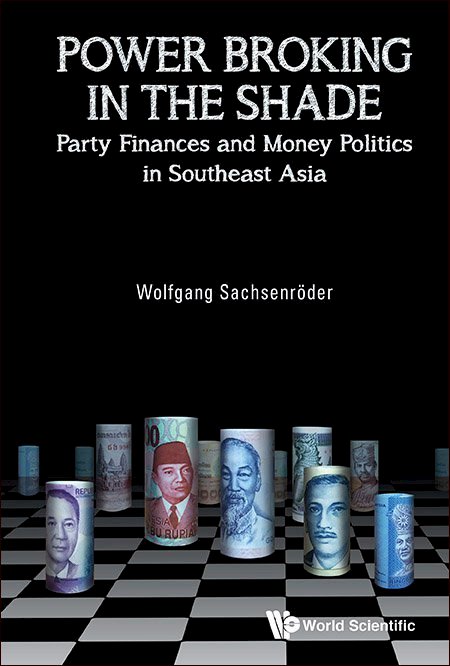

For an overview of party funding practices in Southeast Asia see:

GENERATIVE AI FOR CAMPAIGNING

Perfecting election campaigns with artificial Intelligence?

In the quasi two-party-system of the United Kingdom, focusing the election campaigns on possible swing voters and otherwise relying on secure vote banks, has long been practiced with good results. In some cases, it boiled down to certain streets and certain suburban clusters whenever the parties had sufficient information on the voting patterns in their constituency.

With the increasing volatility of the voting patterns, even in Britain the numbers of swing voters are increasing. Therefore, the campaign methods and instruments must be adapted. On the European continent, the volatility is much higher than in Britain, and the party systems are more and more falling apart. Political parties with faithful membership and reliable vote banks, like Social Democratic or Christian Democratic parties, are shrinking dramatically while fringe parties come and go. Certain policies, e.g. the management or mismanagement of immigration, are being seen by larger parts of the population as a threat and trigger big swings to the right, like in Denmark, Sweden, The Netherlands, France and Germany. The mainstream parties and governments, so far, have no recipe for stemming the tide and often react in panic mode by vilifying the perceived right wingers as Nazis.

In Southeast Asia, many political parties are not offering ideologies in the traditional sense but use ethnic or religious cleavages in their societies as main attraction. The fast-growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) might provide them with new sophisticated instruments to bring the votes out and maximise their voter base.

Scientific American has published an analysis of what may be possible soon. And the advances of social media and available data harvesting methods in Southeast Asia will certainly push the competing parties to try out everything what is available. The low cost of AI generated targeted campaign messages is an additional advantage, while posters and rallies are cost intensive.

The article highlights the danger as well:

“When combined with GenAI’s ability to generate customized messages, this technique places large-scale furtive manipulation within reach of bad-faith political operators or indeed foreign adversaries. Whereas previously, manual targeting at market segments required extensive funding and knowledge, the availability of GenAI has dramatically lowered the cost. Political targeting is now cheaper and easier than ever before.”

The Future of Election Campaigning: The Virtual Battleground

As the saying goes, power corrupts. But the corruption starts or at least tends to start long before the power has been assumed, namely in the election campaigns. Probably, there is no country with a really level playing field for elections in this world. The spoils of power are attractive in the rich countries, where they can be massive, and likewise in the poorest countries, where they might matter even more. The social status and nimbus of a leader is already a perk of sorts, the ability to make decisions for others and to expect their respect and obeisance can create anything between drug-like effects and aphrodisiacs. When Winston Churchill was asked what he was missing the most after being voted out of his premiership in 1945 despite his towering role during WWII, was the sarcasm “transportation”. But everybody who has travelled with top officials will remember this special feeling of privileged transportation.

As a logical consequence, election campaigns can be, and often are, extremely competitive, while seducing many of the players to forget about normal civil fairness. The political cultures, of course, differ from country to country, which means that very different levels of unfairness are possible, often enough ranging from defamation and character assassination to physical assaults like stabbing, poisoning, and shooting.

In Southeast Asia, so far, relatively traditional forms and techniques of election campaigning may be prevailing. Incredible amounts of campaign posters are still in widespread use. Popular leaders and candidates are pulling huge crowds and not so popular ones can hire cheering fake supporters from skilled campaign entrepreneurs. But the traditional media are increasingly losing attraction among the voting masses, newspapers and state-controlled TV stations are no longer the transmitters between the campaigning politicians and their target groups. With the Internet and smart phone penetration reaching even remote areas, more and more voters, especially the younger ones, are getting their political information from social media. And, no surprise, this is exactly the entry point for new trends in marketing, including political campaigning. But at the same time, as the technical opportunities have opened the floodgates for criminal online scams of all sorts and shapes, they attract election campaigners, fair and unfair alike. Why should skilled campaigners not generate thousands of votes if criminals can cheat unsuspecting internet surfers of millions of dollars.

Here are some examples of campaign trends around the world which may give a preview of what Southeast Asia can expect in the next few years, if the tech savvy region should not be even more advanced already.

The newest development first: In the American presidential primaries, deep fake campaigns have already arrived. In the recent New Hampshire primaries, a fake version of President Joe Biden’s voice has been used automatically generated robocalls to discourage Democrats from taking part. As unusual it may sound that the president makes phone call to single voters, the message might influence a sizeable number of voters, nevertheless. As CNN reports, while the audio appears to be fake, it sounds just like the president and even uses his trademark “malarkey” catchphrase.

NB: You can listen to this fake call here: Fake Joe Biden robocall urges New Hampshire voters not to vote in Tuesday’s Democratic primary | CNN Politics

Local candidates in municipal and state elections will probably not resist the temptation of using robocalls. Campaign propaganda in the form of E-mails is common enough for a long time already. For the U.S. presidential campaign, Donie O’Sullivan, CNN’s correspondent covering both politics and technology, predicts an explosion of AI-generated disinformation. Artificial Intelligence has made the upgrading from fake to deepfake so easy that practically anybody can download the necessary program from the Internet and create videos which look authentic for most recipients.

The trend is especially dangerous for the U.S. because the legitimacy of elections and the orderly and peaceful transfer of power has been undermined by Trump’s “big lie” that the 2020 U.S. election was stolen. According to recent polls, nearly 70 per cent of Republicans question the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election. The assumption that Russia had influenced or manipulated this election has never been proven but was popular enough for the media to be repeated for many months.

Another related incident is brand-new and all over the media, especially with the war In Ukraine being discussed controversially in Germany. End of January, a news magazine reported that Internet experts of the Foreign Office have detected no less than 50.000 fake accounts on social media platform X, trying to stir anger at Berlin’s support for Ukraine.

In Southeast Asia, the election triumph of President Marcos in June 2022 was reportedly facilitated, among others, by thousands of occasional volunteers who could make a few bucks with their smart phones during the campaign.

The social media scene, however, is changing very fast. This is evident in the number of followers of the candidates in the ongoing presidential campaign in Indonesia. While front-runner Prabowo has 10 million followers on Facebook, 6.7 Million on Instagram and none on TikTok, his much younger vice-presidential candidate Gibran has only 173.000 on “old-fashioned Facebook, 1.4 million on Instagram and 446,900 on TikTok. It looks like a mirror of the generation gap with Facebook something for the older generation. But middle-aged PDI-P candidate Ganjar Pranowo, born in 1968, is the champion on TikTok with remarkable 7.1 million followers in December last year. They are all fighting on the virtual battleground, though posters and rallies are still an important and expensive part of the campaign.

Understanding Thai politics

A warmly recommended assessment of the current political situation in Thailand:

https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2714889/politics-parties-and-pms

Happy 2024

Whether party politics can make you happy is debatable and depends a lot on which end you participate. Losing an election is no fun at all, winning one can trigger anything from euphoria to arrogance, and the same is true for helping in election campaigns. Observers and analysts like political scientists risk an impact to their mood as well.

For any role or outcome, we recommend a wise decision by the French enlightenment

writer, philosopher, and satirist Voltaire:

J’ai décidé d’être heureux, parce que c’est bon pour la santé

I have decided to be happy because that is good for my health

All the best and good health!

Your Political Partyforum Southeast Asia

The Ever-Increasing Commercialization of Election Campaigns and Party Politics

In an article published by the Straits Times on 18 December, Wahyudi Soeriaatmadja, the Indonesia Correspondent of Singapore’s flagship daily, describes in detail his observations during the ongoing presidential election campaign. (LINK: Hired crowds in demand for Indonesia political rallies | The Straits Times). These observations are so interesting because the phenomenon of more and more professional and commercialized election campaigning and party politics is spreading to many places and continents. What is especially exciting here is the fabulous Indonesian creativity in this field.

The article describes how Mr Lukman, a 45-year-old parking attendant, runs his “rent-a-crowd” service. Once hired by a candidate or party, Lukman gathers at least 200 persons and brings them by bus to the event. He charges 100.000 rupiah (6,5 USD) per “supporter” plus food and bus transport.

Great care must be taken to pick people who look like real and enthusiastic supporters. Lukman selects the ones “who wear tidy clothes, those who look like college students, the 18-year-olds, the zillennials.” Obviously, many of the 200 million voters are already suspicious of the fake supporters, so the hired ones must act up real enthusiasm, cheer and dance. Since the salary is paid only after the event, not sufficiently convincing supporters risk a part of their pay.

Often enough, the hired troops don’t know who they are supposed to cheer until they arrive at the venue. For them, of course, it does not matter, they are like the extras in mass scenes film shootings. So, the “industry” is facing an increasing demand for sincere and convincing cheering support. A spokesman for the ruling Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), told The Straits Times that the party does not use and has never tolerated such services. True or not, it is a basic fact, that money is a decisive requirement of election campaigning, of course not only in Indonesia. But the democratic development of the country has seen several creative solutions to candidacy and electoral success, up to the phenomenon that rich candidates can choose among competing parties for a promising slot.

In Europe with a century-long history of political parties and the corresponding political theory, the developments are comparable to the ones in Southeast Asia, except for the fake cheering crowds, hired for the occasion. Campaign events, even with prominent speakers, ministers and prime ministers, risk looking bad on pictures and TV videos because, often enough, the expected crowds are not materializing. And most of the traditional campaign features are provided by PR agencies anyway. The party members sacrificing evenings and nights for hanging campaign posters are practically history. That is being accompanied by shrinking party membership in most European countries. The once dominating Christian Democrats of Italy have disappeared, once struggling right-wing parties are growing and booming in many countries, like recently in the Netherlands, mainly because voters are frightened by uncontrolled immigration. In Germany, the 160-years-old Social Democratic Party, is continuously shrinking in membership and polling results, though still in an uneasy coalition with Greens and Liberals under a social-democratic chancellor. A workers’ party for most of its life, the SPD is no longer seen as fighting for the working class or the little man on the street. Consequently, during the last few decades, the internal social coherence of the party has changed dramatically. Still some fifty or seventy years ago, the small local branches offered a sort of family bonding, the members knowing each other, and the local treasurer visiting the members at home to collect the monthly membership fees. All that is history, of course, and that has direct repercussions for the ideological and programmatic consistency of the SPD and many similar parties. Probably, the changing party landscapes are less based on values, programs, and group-interest but more dependent on professional management, financial resources, political psychology, and the real or media-hyped charisma of the leaders.

For Southeast Asia see:

What makes a good political leader?

We vote regularly, at least a majority of us, and we try to gauge the candidates – probably first – and their programs or ideologies – probably not so carefully. Election choices are to a high degree emotional and the popularity of political leaders as well. And how do we see our elected leaders after a year in office or after major bad decisions? Do we learn over the years to be more careful? The long queue of bad leaders in too many countries seems to suggest that voters, as prominent leaders have said, are terribly stupid and awfully forgetful…

Partyforumseasia recommends the following article from The Conversation UK:

What makes a good political leader – and how can we tell before voting?

October 11, 2023

For many people, voting is not just a right, it’s an act of civic duty. Even more than that, some voters base their decisions on what they believe best serves society as a whole, not what might personally advantage them.

The trick, of course, is how to exercise that vote in a responsible, informed and considered manner. Understanding the policies of different parties is obviously a key part of that, in which case resources such as Policy.nz and Vote Compass can be helpful.

But what of the individual characteristics of candidates and would-be leaders? What can the research tell us about what to look for? Given they are “actors” on the political “stage”, how do we evaluate their performance?

Of course, leadership isn’t a solo act. Many things determine what leaders can and can’t do. But what makes them tick – how their personality or character informs their actions – is enduringly fascinating. In fact, we know a lot about the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that can help distinguish between good and bad leaders.

Confusing confidence with competence

Given “good” leadership is generally accepted as being both ethical and effective, it stands to reason “bad” leaders tend to fail on one or both counts. They either breach accepted principles of ethical or moral conduct, or they act in ways that detract from achieving desired results.

This distinction helps demystify leadership by highlighting that the qualities we least admire in others are also what scholars have long flagged as danger signs in leaders: arrogance, vanity, dishonesty, manipulation, abuse of power, lack of care for others, cowardice and recklessness.

Read more: Romantic heroes or ‘one of us’ – how we judge political leaders is rarely objective or rational

Notably, though, bad leaders can appear charming, confident and driven to achieve, despite seeking power for selfish reasons.

Numerous studies have identified the ways in which narcissists and what are sometimes called corporate psychopaths can be highly skilled at manipulating people into believing they’ve got what it takes, but will typically lead in destructive and dysfunctional ways. Other studies have shown the negative effects of “Machiavellian” leadership styles.

There is also a tendency to confuse competence – the actual knowledge and skills needed to perform a leadership role – with confidence. Good leaders tend to be relatively humble about their abilities and knowledge. This means they’re better listeners, more sensitive to others’ needs, and better able to collaborate effectively.

Practical wisdom

None of this fascination with leadership is new. The Classical Greek philosopher Aristotle argued good leaders possess a range of character virtues in the “middle ground” between what he called the “vices” of excess or deficiency. Courage, for example, is the virtuous mid-point between the vices of recklessness and cowardice.

The modern character virtues leadership researchers emphasise include humanity, humility, integrity, temperance, justice, accountability, courage, transcendence, drive and collaboration.

Each attribute helps a leader deal more effectively with some aspect of their role. Humanity, for instance, enables a leader to be considerate, empathetic and compassionate. Temperance helps them remain calm, composed, patient and prudent, even in testing circumstances.