We vote regularly, at least a majority of us, and we try to gauge the candidates – probably first – and their programs or ideologies – probably not so carefully. Election choices are to a high degree emotional and the popularity of political leaders as well. And how do we see our elected leaders after a year in office or after major bad decisions? Do we learn over the years to be more careful? The long queue of bad leaders in too many countries seems to suggest that voters, as prominent leaders have said, are terribly stupid and awfully forgetful…

Partyforumseasia recommends the following article from The Conversation UK:

What makes a good political leader – and how can we tell before voting?

October 11, 2023

For many people, voting is not just a right, it’s an act of civic duty. Even more than that, some voters base their decisions on what they believe best serves society as a whole, not what might personally advantage them.

The trick, of course, is how to exercise that vote in a responsible, informed and considered manner. Understanding the policies of different parties is obviously a key part of that, in which case resources such as Policy.nz and Vote Compass can be helpful.

But what of the individual characteristics of candidates and would-be leaders? What can the research tell us about what to look for? Given they are “actors” on the political “stage”, how do we evaluate their performance?

Of course, leadership isn’t a solo act. Many things determine what leaders can and can’t do. But what makes them tick – how their personality or character informs their actions – is enduringly fascinating. In fact, we know a lot about the beliefs, attitudes and behaviours that can help distinguish between good and bad leaders.

Confusing confidence with competence

Given “good” leadership is generally accepted as being both ethical and effective, it stands to reason “bad” leaders tend to fail on one or both counts. They either breach accepted principles of ethical or moral conduct, or they act in ways that detract from achieving desired results.

This distinction helps demystify leadership by highlighting that the qualities we least admire in others are also what scholars have long flagged as danger signs in leaders: arrogance, vanity, dishonesty, manipulation, abuse of power, lack of care for others, cowardice and recklessness.

Read more: Romantic heroes or ‘one of us’ – how we judge political leaders is rarely objective or rational

Notably, though, bad leaders can appear charming, confident and driven to achieve, despite seeking power for selfish reasons.

Numerous studies have identified the ways in which narcissists and what are sometimes called corporate psychopaths can be highly skilled at manipulating people into believing they’ve got what it takes, but will typically lead in destructive and dysfunctional ways. Other studies have shown the negative effects of “Machiavellian” leadership styles.

There is also a tendency to confuse competence – the actual knowledge and skills needed to perform a leadership role – with confidence. Good leaders tend to be relatively humble about their abilities and knowledge. This means they’re better listeners, more sensitive to others’ needs, and better able to collaborate effectively.

Practical wisdom

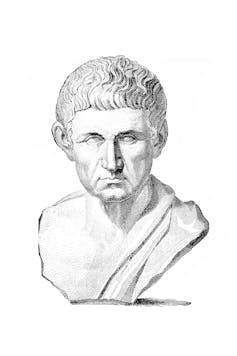

None of this fascination with leadership is new. The Classical Greek philosopher Aristotle argued good leaders possess a range of character virtues in the “middle ground” between what he called the “vices” of excess or deficiency. Courage, for example, is the virtuous mid-point between the vices of recklessness and cowardice.

The modern character virtues leadership researchers emphasise include humanity, humility, integrity, temperance, justice, accountability, courage, transcendence, drive and collaboration.

Each attribute helps a leader deal more effectively with some aspect of their role. Humanity, for instance, enables a leader to be considerate, empathetic and compassionate. Temperance helps them remain calm, composed, patient and prudent, even in testing circumstances.

Deployed together, these character virtues help foster sound judgment, insight, decisiveness – allowing a leader to calmly handle complex, unfolding challenges.

For Aristotle, the ideal leader could demonstrate what he called “phronesis”, or practical wisdom. This wasn’t necessarily about delivering perfect, painless solutions. Indeed, phronesis might mean adopting the least-worst option – which is often the case when dealing with the complex task of running a country.

There is also no single personality “type” most suited to good leadership. But studies indicate those who are proactive, optimistic, believe in themselves and can manage their anxieties stand a better chance. Empathy, a sense of duty and a commitment to upholding positive social values also underpin the attributes of good leaders.

Evaluating political leadership

No leader will be perfect. But each character or personality flaw impedes their capacity for wise judgment and dealing with the demands of their role. A wise leader, therefore, is one who has deep and accurate insight into their personal foibles and has strategies to mitigate for those tendencies.

Political leaders will obviously seek to present their policies, parties and themselves in a positive light, something known as “impression management”. This is where critical questioning and fact checking by journalists and experts can play a vital role.

But gauging a leader’s “true” personality or character is more difficult. And we first need to be aware that our impressions and evaluations of leaders are not entirely driven by reason or logic.

Secondly, we can look for recurring patterns of behaviour in different situations over time. We should pay particular heed to behaviour under pressure, when it becomes more difficult to “mask” true feelings and motives.

Thirdly, we can consider the values that underpin a leader’s policies, who benefits from them, and what messages these convey to the community at large.

In the long run, a leader’s results bear consideration. But we need to assess these fairly, accounting for what was beyond their control. We should be mindful to avoid “hindsight bias” – the tendency to imagine events were predictable because we know they’ve occurred.

It should be no surprise that what constitutes good leadership has been studied and debated for thousands of years. Leaders have power and we’ve always wanted them to use it wisely. An informed voting choice makes that more likely.