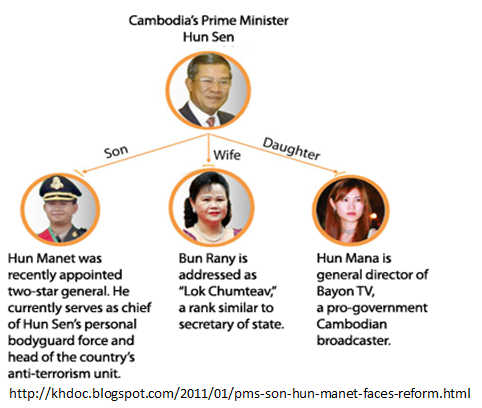

Millenia of feudalism have left parts of their legacy until today. As it was normal that princelings were groomed to become kings or sultans, company owners often groom their children as successors. Should it be different in politics? It probably should, because charisma and eloquence paired with intelligence and a sense of chosenness and mission are not necessarily hereditary. However, political dynasties are common, from the Kennedy and Bush clans in the USA, the Gandhi family in India, to the latest well prepared and successful handing over of the Cambodian premiership from Hun Sen to his son Hun Manet.

The Indonesian media headlines last week sounded somewhat skeptical when President Jokowi’s youngest son Kaesang Pangarep, 28, was named as chairman and leader of the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI) on 25th September, only a few days after joining. The PSI, founded in 2014, tries to form a counterbalance to the traditional macho and money style politics, eying the young and progressive voter generation, in a way similar to the Move Forward Party in Thailand. It is not yet represented in the national parliament but in several regional and provincial parliaments as well as in the municipal councils of big cities like Surabaya and Bandung. The party is sort of revolutionary with its 45 per cent of female candidates and the transparent way of publicly selecting the candidates.

One interesting feature which has come up in Indonesia’s democratic development is the focus on eligibility in the selection of candidates. It has the disadvantage of giving attractive candidates a choice between different parties and their financial possibilities – or a rich candidate “buying” a poor party as a vehicle for his ambition. But the focus on eligibility is a feature which many European parties should keep in mind as well. Their candidates for party posts and parliamentary elections are too often making their way up through the ranks from the bottom. This needs elbows, ambitions and years of patience, compromises, and back-door deals, which in many cases does not produce candidates sufficiently attractive for the voters.

For the Indonesian party scene, the lightning career of Kaesang Pangarep makes sense. As the president’s son he is highly visible and known to the broader public which will be useful for the PSI in the upcoming elections next year.

With Kaesang’s career move, the Widodo family’s political life after the president’s second term does not end in 2024. Jokowi’s elder son Gibran Rakabuming Raka is already the mayor of Surakarta, and Bobby Nasution, his son in law, is mayor of Medan. Both are on a PDI-P ticket and the PSI-move for Kaesang has been interpreted as a rift between President Widodo and PDI-P chair Megawati, his sponsor.

Back to the addictive attraction of power and high office. Both are addictive in terms of status and self-importance, sometimes with access to funding on top. Giving up the presidency of big countries like Indonesia, but any smaller office as well, may create a sort of phantom pain, the loss of something the holder is used to and eventually feels entitled to. When Winston Churchill was no longer prime minister, a reporter asked him what he missed most. With grim humour Churchill answered in one word: “Transportation…”